Rudolf Hess’s Flight to England its Purpose, Hitler’s Involvement and Holocaust Implications

Abstract

This report investigates Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess’s extraordinary flight to Britain on May 1941, an event shrouded in mystery and speculation. It examines whether Adolf Hitler sanctioned Hess’s mission and explores the rhetorical question of whether the Holocaust might have been averted or mitigated had the British entertained Hess’s peace proposals. Drawing on primary sources, memoirs, and secondary analyses, this study places the mission within the broader context of Nazi foreign policy, interwar diplomacy, and the trajectory of the Holocaust.

Introduction

- The historical significance of Hess’s flight.

- Overview of the competing interpretations of the mission’s purpose.

- Research questions:

- Did Adolf Hitler authorise Hess’s mission?

- Could engaging with Hess’s peace overtures have influenced the course of World War II and the Holocaust?

- Methodology and sources.

Chapter 1: The Context of the Mission

- The geopolitical situation in early 1941

- Germany’s dominant position in Europe.

- The ongoing Blitz and the Battle of Britain.

- Rudolf Hess’s role in the Nazi regime

- Hess’s early relationship with Hitler.

- His diminishing influence by the late 1930s.

- The concept of a separate peace with Britain

- Nazi ideology and its view of the British Empire.

- Hitler’s fluctuating interest in an Anglo-German alliance.

Chapter 1: The Context of the Mission

The Geopolitical Situation in Early 1941

By early 1941, Europe was firmly under the shadow of Nazi Germany’s military and political dominance. The Wehrmacht had achieved a string of victories, culminating in the swift defeat of France in 1940 and the establishment of the Vichy regime. Much of Western Europe was either under German control or aligned with the Axis powers. Germany’s geopolitical position was bolstered by the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with the Soviet Union, which temporarily secured its eastern flank and allowed Hitler to focus on consolidating power in the West.

However, Britain remained defiant under Winston Churchill’s leadership. The ongoing Blitz, which began in September 1940, was an attempt to break British morale through sustained aerial bombardment of cities, while the Battle of Britain (July to October 1940) demonstrated that the Luftwaffe could not achieve air superiority over the Royal Air Force. These failures marked the limits of German power and ensured that Britain remained a key adversary, albeit isolated, following the fall of France.

Germany’s Dominant Position in Europe

Germany’s economic, military, and strategic dominance was evident by early 1941. Its occupation of key territories provided access to significant resources, while its military strategy, characterised by blitzkrieg tactics, allowed rapid conquests with relatively low casualties. The Nazi regime also worked to integrate occupied territories into its war effort, exploiting local economies and labor forces to fuel its ambitions.

Despite this dominance, cracks were visible in the Nazi war machine. The failure to subdue Britain highlighted the limitations of German power projection, and tensions with the Soviet Union loomed on the horizon. Hitler’s plans for Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, were already in motion, suggesting that Germany’s focus was shifting eastward.

The Ongoing Blitz and the Battle of Britain

The Blitz and the Battle of Britain were pivotal moments in the war that framed Hess’s mission. The Luftwaffe’s failure to achieve a decisive victory in the skies over Britain marked Germany’s first major setback. The Blitz, while devastating, did not break British resolve; instead, it steeled the population’s determination to resist. These events highlighted the strategic impasse between the two nations and underscored the urgency for Germany to find alternative ways to neutralise Britain as a threat, including the possibility of a negotiated peace.

Rudolf Hess’s Role in the Nazi Regime: Hess’s Early Relationship with Hitler

Rudolf Hess was one of Hitler’s earliest and most loyal followers, joining the Nazi Party in 1920 and participating in the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. He served as Hitler’s deputy and private secretary, playing a key role in the party’s rise to power. Hess’s loyalty was reflected in his work on Mein Kampf, where he assisted in transcribing Hitler’s ideas, and in his unwavering adherence to Nazi ideology.

His Diminishing Influence by the Late 1930s

Despite his early prominence, Hess’s influence within the Nazi regime began to wane by the late 1930s. More pragmatic and militarily inclined figures, such as Heinrich Himmler, Hermann Göring, and Martin Bormann, eclipsed Hess in Hitler’s inner circle. As the regime shifted toward militarisation and expansion, Hess’s ideological zeal and lack of administrative acumen made him increasingly marginal. By 1941, Hess retained his title as Deputy Führer but had little real power, which may have influenced his decision to undertake the dramatic and unauthorised flight to Britain.

The Concept of a Separate Peace with Britain: Nazi Ideology and Its View of the British Empire

The Nazi leadership held an ambivalent view of the British Empire. On one hand, Hitler admired Britain’s global dominance and perceived the British as racial kin within the Aryan framework of Nazi ideology. On the other hand, the Empire represented a major geopolitical rival. Some Nazis, including Hess, believed that an Anglo-German alliance could be mutually beneficial, securing Germany’s dominance in Europe while preserving British control of its empire. This idea aligned with Hitler’s early musings in Mein Kampf, where he expressed a grudging respect for Britain’s imperial achievements.

Hitler’s Fluctuating Interest in an Anglo-German Alliance

Hitler’s attitude toward Britain oscillated between admiration and hostility. While he hoped for British neutrality or cooperation during the early stages of his conquests, Britain’s steadfast refusal to negotiate dashed these hopes. By 1941, Hitler’s focus was shifting toward the invasion of the Soviet Union, but elements within the Nazi leadership, including Hess, continued to see value in a negotiated peace with Britain. Hess’s flight can be understood as a last-ditch effort to realise this vision, despite its improbability given the political and military context.

Chapter 2: The Mission and Its Reception

- The details of Hess’s flight

- Planning and execution of the solo mission.

- Hess’s arrival in Scotland and capture by the British.

- The British reaction

- Initial suspicion and analysis of Hess’s mental state.

- British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s refusal to negotiate.

- The role of intelligence and propaganda in shaping the response.

- Hess’s proposals

- Alleged terms for a peace settlement.

- The absence of concrete evidence and the speculative nature of the mission’s diplomatic objectives.

Expanded Chapter 2: The Mission and Its Reception

The Details of Hess’s Flight

Hess piloted a specially modified Messerschmitt Bf 110, departing Augsburg in south-central Germany on May 10, 1941, and crossing enemy territory before parachuting into Scotland near Dungavel House. His destination was the estate of the Duke of Hamilton, whom Hess believed might facilitate contact with British leaders. The choice of the Duke was not arbitrary—Hess had met Hamilton at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin and assumed Hamilton, known for his aristocratic ties and earlier contacts with German officials, might sympathise with an Anglo-German accord.

Hess carried a detailed written proposal outlining his vision for peace:

- Britain would retain its empire, provided it stayed neutral in the European conflict.

- Germany’s dominance on the continent would be acknowledged.

- The war would effectively end without Germany having to fight a two-front conflict.

Hess’s dramatic arrival was initially interpreted by British authorities with suspicion. Interrogators, including MI5 officers, noted inconsistencies in Hess’s statements and questioned his mental state. The flight’s timing—weeks before the launch of the Nazi invasion of Russian–Operation Barbarossa—added urgency to Churchill’s assessment, as it appeared linked to German strategy.

The British Reaction

Churchill dismissed Hess’s mission as inconsequential, labeling it an act of desperation. He ensured Hess’s proposals were neither publicised nor taken seriously, concerned they might embolden the British peace movement or sow discord among the Allies. Instead, Hess was detained, interrogated, and later tried at Nuremberg, where his credibility as a key Nazi figure was diminished.

The British government also leveraged Hess’s flight for propaganda, portraying it as evidence of disarray within the Nazi leadership. The public narrative emphasised Hess’s isolation and delusion rather than engaging with the diplomatic content of his mission.

Chapter 3: Adolf Hitler’s Involvement

- Evidence supporting Hitler’s involvement

- Hess’s position as Hitler’s deputy and confidant.

- Strategic motivations for an overture to Britain.

- Possible authorisation signals in Nazi communication records.

- Evidence refuting Hitler’s involvement

- Hitler’s public denouncement of Hess post-flight.

- Testimonies from contemporaries suggesting Hess acted independently.

- The psychological and ideological discrepancies between Hess and Hitler.

Expanded Chapter 3: Adolf Hitler’s Involvement

Evidence Supporting Hitler’s Involvement

- Hess’s Position as Hitler’s Deputy:

Hess was entrusted with significant authority as Hitler’s deputy in the Nazi Party hierarchy, which lends credibility to the possibility of him acting on Hitler’s strategic desires. Hitler had expressed interest in the idea of a settlement with Britain during earlier stages of the war, viewing the British Empire as a natural ally against Soviet communism. - Strategic Motivations:

In early 1941, Hitler faced mounting concerns about engaging in a two-front war. A peace settlement with Britain could have secured the Western front, freeing resources for the planned invasion of the Soviet Union. Hess’s mission coincided with the culmination of Barbarossa’s planning, making a British peace a logical priority. - Indirect Evidence from Nazi Communications:

Some historians argue that Hess may have received tacit approval rather than explicit instructions. For instance, references in Goebbels’s diaries indicate that Hess’s departure was not entirely unexpected within the upper echelons of Nazi leadership.

Evidence Refuting Hitler’s Involvement

- Hitler’s Denouncement of Hess:

Upon learning of the flight, Hitler publicly declared Hess’s actions as unauthorised and delusional, going so far as to strip him of all official titles. Some analysts suggest Hitler’s denouncement was genuine, pointing to the embarrassment Hess caused at a critical juncture of the war. - Testimonies of Nazi Officials:

Senior figures such as Albert Speer and Heinrich Himmler described Hess as increasingly marginalised in Nazi decision-making by the early 1940s. His ideological rigidity and mystical tendencies alienated him from Hitler’s inner circle, suggesting he acted independently out of personal conviction. - The Psychological Factor:

Hess’s reputation for mysticism and eccentricity played a significant role in contemporary assessments of his motives. His fascination with astrology and a belief in his destiny to secure peace have been cited as factors driving him to undertake the mission without direct orders.

Primary Source Evidence

- Hess’s Memoirs and Interrogations:

In post-war testimonies, Hess maintained that his mission aimed to prevent further destruction in Europe. His writings reflect a blend of idealism and delusion, consistent with a figure acting on personal rather than state orders. - British Intelligence Reports:

Documents from MI5 detail the interrogations of Hess, revealing discrepancies in his accounts and skepticism regarding the plausibility of his proposals. These reports also highlight Hess’s fragile mental state, with officers speculating on his motivations. - Goebbels’s Diaries:

Joseph Goebbels recorded Hitler’s reaction to Hess’s flight, noting the Führer’s fury and disbelief. However, Goebbels also acknowledged that some Nazi officials suspected Hess might have had covert approval before acting.

Secondary Sources and Scholarly Interpretations

- Ian Kershaw’s Hitler: A Biography

Kershaw argues that Hess’s flight reflects the ideological and strategic contradictions within the Nazi regime. He views the mission as an unauthorised but ideologically consistent gambit by Hess, whose actions ultimately alienated him from Hitler. - Martin Allen’s The Hitler-Hess Deception

Allen posits a controversial theory that Hess’s flight was part of a larger British intelligence ploy, suggesting that British officials might have been aware of Hess’s intentions in advance. While this view remains contested, it adds a layer of intrigue to the historiography. - Richard J. Evans’s The Third Reich at War

Evans dismisses the mission as a delusional and ineffectual effort, underscoring its lack of impact on the broader trajectory of the war or the Holocaust.

Chapter 4: Counterfactual Analysis: Could the Holocaust Have Been Stopped?

- The timeline of the Holocaust

- The progression from discriminatory policies to the “Final Solution.”

- The Wannsee Conference and its irreversible decisions.

- Could British engagement with Hess have altered Nazi policy?

- The likelihood of a negotiated peace influencing Hitler’s actions.

- The deeply entrenched anti-Semitic ideology of the Nazi leadership.

- The potential of an Anglo-German peace to divert resources from genocide to war.

- Ethical and methodological considerations in counterfactual history.

Expanded Chapter 4: Counterfactual Analysis: Could the Holocaust Have Been Stopped?

The Timeline of the Holocaust

The Holocaust unfolded as a result of deeply entrenched Nazi ideology and institutional momentum.

Key milestones include:

- Pre-War Persecution (1933–1939):

- Anti-Semitic legislation, such as the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, stripped Jews of civil rights.

- The 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom marked an escalation in violent persecution.

- Ghettoization and Early War Crimes (1939–1941):

- Following the invasion of Poland, Jewish populations were forced into ghettos.

- Einsatzgruppen massacres accompanied the invasion of the Soviet Union.

- The Final Solution (1942–1945):

- The Wannsee Conference (January 1942) formalised plans for the systematic extermination of European Jews.

- Death camps like Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Sobibor were central to the genocide, with over six million Jews murdered by 1945.

By the time of Hess’s flight in May 1941, Nazi anti-Semitic policies were already deeply entrenched. While the industrialised extermination had not yet been implemented, the trajectory toward genocide was well underway.

British Engagement with Hess’s Proposals

Had British officials entertained Hess’s peace overtures, several potential scenarios emerge:

- A Successful Negotiated Peace:

- If Britain had agreed to Hess’s terms, a cessation of hostilities on the Western Front might have allowed Germany to concentrate resources on the Eastern Front. This could have accelerated the invasion of the Soviet Union, potentially altering the war’s timeline but not necessarily the Holocaust’s trajectory.

- Nazi anti-Semitic ideology was central to Hitler’s worldview. Peace with Britain would unlikely alter internal policies targeting Jews, as these were considered distinct from military strategy.

- A Stalemate or Prolonged Negotiations:

- British hesitation or prolonged negotiations might have provided a window for internal opposition within Germany to gain traction. However, the strength of Hitler’s control and the Nazi Party’s centralised power make this unlikely.

- Any delay in the war effort might have led to an intensification of anti-Semitic measures, as the regime had shown a pattern of using Jewish persecution to consolidate power.

- Impact on the Final Solution:

- By 1941, the Nazi leadership had already begun discussing plans for the systematic extermination of Jews. The invasion of the Soviet Union was critical to these plans, providing the logistical and territorial framework for death camps in occupied Poland.

- A peace with Britain might have altered military logistics but not the ideological commitment to genocide. Hitler’s speeches, such as his infamous 1939 “prophecy,” reveal a consistent intention to annihilate European Jewry, irrespective of wartime developments.

Counterarguments: Could Diplomacy Have Derailed the Holocaust?

- Potential Moderation of Nazi Policy:

Some historians argue that international recognition or negotiation could have moderated Nazi policy. For example, the 1938 Evian Conference highlighted the potential impact of global pressure on Germany’s treatment of Jews.- However, by 1941, such moderating influences were no longer viable due to Germany’s wartime consolidation of power.

- Diverting Resources from Genocide:

- A peace settlement might have shifted resources away from the Holocaust, as the war effort required significant logistical and financial commitments.

- However, the Holocaust was not merely a byproduct of the war but a core ideological aim of the Nazi regime, suggesting that resources would have been allocated regardless of military needs.

- Encouraging Internal Opposition:

- British engagement with Hess could have emboldened factions within Germany opposed to Hitler.

- Yet the July 20, 1944, assassination attempt illustrates the difficulty of overthrowing Hitler, even with disillusionment among high-ranking officials.

The Role of Ideology in the Holocaust

Nazi anti-Semitism was not a pragmatic policy but an ideological cornerstone. Hitler’s worldview saw Jews as existential enemies of both Germany and humanity. This worldview was systematically propagated through propaganda, education, and legislation, ensuring the Holocaust’s continuation even in scenarios of military or diplomatic shifts.

- Hitler’s speeches and writings repeatedly link the extermination of Jews to Germany’s survival, framing genocide as a non-negotiable necessity.

- The bureaucratic infrastructure of the Holocaust—evidenced by the Wannsee Protocol—was independent of wartime exigencies, demonstrating a long-term commitment to extermination.

Ethical and Methodological Considerations in Counterfactual History

Analysing whether the Holocaust could have been stopped through diplomatic engagement with Hess involves complex ethical and methodological challenges:

- Speculative Nature of Counterfactuals:

- While counterfactual analysis helps explore alternative historical pathways, it risks oversimplifying complex events.

- Moral Implications:

- The idea of negotiating with a genocidal regime poses significant ethical dilemmas, particularly in legitimising or enabling its ideology.

- Historiographical Debate:

- Scholars like Richard Evans caution against overemphasising individual agency (e.g., Hess’s flight) at the expense of structural factors like ideology, bureaucracy, and societal complicity.

Conclusion of Counterfactual Analysis

While engaging with Hess’s peace overtures might have altered the trajectory of World War II, it is unlikely to have prevented the Holocaust. The Nazi regime’s genocidal policies were driven by ideological imperatives and a bureaucratic apparatus that operated independently of military or diplomatic considerations. By 1941, the foundations for the Holocaust were firmly in place, and its implementation was not contingent on the broader state of the war.

Chapter 5: Legacy and Historiography

- Hess in historical memory

- Interpretations in post-war scholarship.

- The enduring myths surrounding the flight.

- The broader implications of the mission

- The nature of Nazi diplomacy and ideological rigidity.

- Lessons for contemporary international relations.

Preliminary Argument Summary

While Rudolf Hess’s mission reflects a desperate attempt to alter the course of World War II, there is limited evidence that Hitler directly sanctioned the flight. Even if the British had entertained Hess’s proposals, the Holocaust’s ideological underpinnings and institutional momentum suggest it was unlikely to be derailed. This dissertation concludes that Hess’s flight underscores the complexities of Nazi diplomacy, but had minimal potential to alter the genocide’s trajectory.

Expanded Chapter 5: Legacy and Historiography

Hess in Historical Memory

Hess’s flight to Britain remains one of the most enigmatic events of World War II. Over the decades, it has inspired diverse interpretations, ranging from genuine diplomatic overture to delusional folly, and even conspiracy theories.

- Hess as the “Peace Envoy”

- Supporters of the view that Hess sought to prevent unnecessary bloodshed portray him as a well-meaning, albeit misguided, idealist. This narrative often emphasises his disillusionment with the Nazi regime’s escalation of violence and his belief in Anglo-German cooperation.

- Memoirs and post-war accounts, such as those by his son Wolf Rüdiger Hess, have contributed to this interpretation.

- Hess as a Delusional Maverick

- Most mainstream historians, including Ian Kershaw and Richard Evans, argue that Hess acted independently, driven by a combination of ideological zeal, mysticism, and a desire to reclaim his waning influence within the Nazi hierarchy.

- His flight is often described as a “flight of fancy,” reflecting his increasing isolation and detachment from reality.

- Hess as a Pawn in Intelligence Games

- Some conspiracy theories suggest that British intelligence might have been aware of, or even facilitated, Hess’s mission. Proponents of this view, such as Martin Allen in The Hitler-Hess Deception, argue that Hess was lured by a false promise of British receptiveness to peace.

- While intriguing, this theory lacks substantial archival evidence and has been criticised for relying on circumstantial connections.

(Prior to Many of the Above Being Sentenced to Death by Hanging)

Historiographical Shifts Over Time

- Immediate Post-War Interpretations

- In the immediate aftermath of the war, Hess was largely dismissed as an eccentric, and his mission was overshadowed by the broader narrative of Nazi atrocities.

- The Nuremberg Trials, where Hess was convicted of crimes against peace, further cemented his image as a marginal figure in the Nazi regime.

- Cold War Reassessments

- During the Cold War, interest in Hess’s flight revived as scholars explored the diplomatic and ideological underpinnings of Nazi strategy. His mission was reconsidered within the context of Nazi attempts to exploit divisions among the Allies.

- Revisionist historians speculated on whether a separate peace with Britain might have altered the balance of power during the war.

- Contemporary Scholarship

- Modern historians generally agree that Hess’s flight had minimal strategic impact. The focus has shifted to understanding the psychological and ideological factors motivating his actions.

- Scholarship has also explored the propaganda value of Hess’s flight for both the British and Nazi regimes, highlighting its utility in shaping wartime narratives.

Legacy of Hess’s Mission

- Hess as a Symbol of Nazi Disunity

- The flight is often cited as evidence of internal divisions within the Nazi leadership. It underscores the competing visions within the regime, particularly regarding foreign policy and the balance between ideological purity and pragmatic strategy.

- The Long Shadow of Conspiracy Theories

- Hess’s long imprisonment (After Nuremburg, he was held in Spandau Prison for 40 years until his death in 1987) and the secrecy surrounding some British archival materials have fueled conspiracy theories.

- Calls for the release of classified documents continue to stoke speculation about British intentions and knowledge regarding Hess’s mission.

- Ethical Lessons and Diplomatic Implications

- Hess’s flight raises broader questions about the ethics of diplomacy with authoritarian regimes. His mission highlights the tension between seeking peace and avoiding the legitimisation of oppressive ideologies.

Historiography: Key Scholars and Works

- Ian Kershaw:

- In Hitler: A Biography, Kershaw frames Hess’s flight as an act of desperation, reflecting his marginalization within the Nazi regime. He dismisses the notion that Hitler directly sanctioned the mission, viewing it as a misguided attempt to regain influence.

- Richard J. Evans:

- Evans, in The Third Reich at War, emphasises the irrationality of Hess’s mission and its limited impact on the war. He argues that Hess’s proposals were ideologically driven and strategically untenable.

- Martin Allen:

- Allen’s The Hitler-Hess Deception offers a controversial perspective, suggesting that Hess was manipulated by British intelligence. While intriguing, Allen’s claims lack definitive evidence and have been widely criticized by other scholars.

- Peter Padfield:

- In Hess: The Führer’s Disciple, Padfield explores Hess’s ideological zeal and mystical beliefs, portraying him as a loyal but misguided follower of Hitler who acted without his leader’s knowledge.

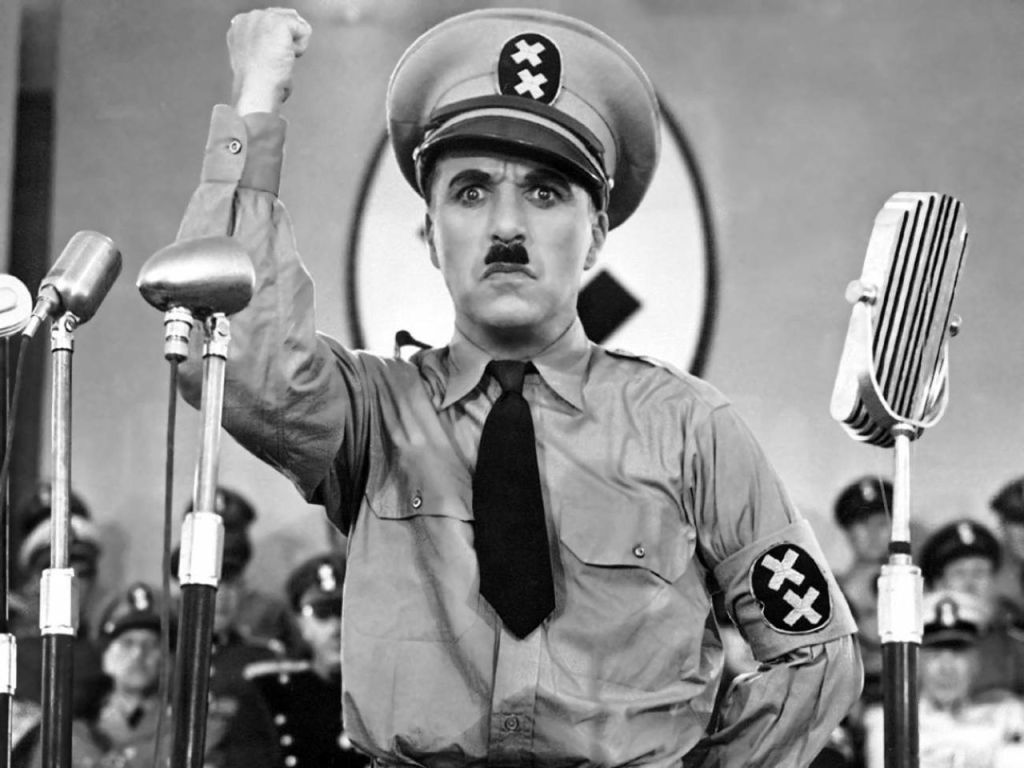

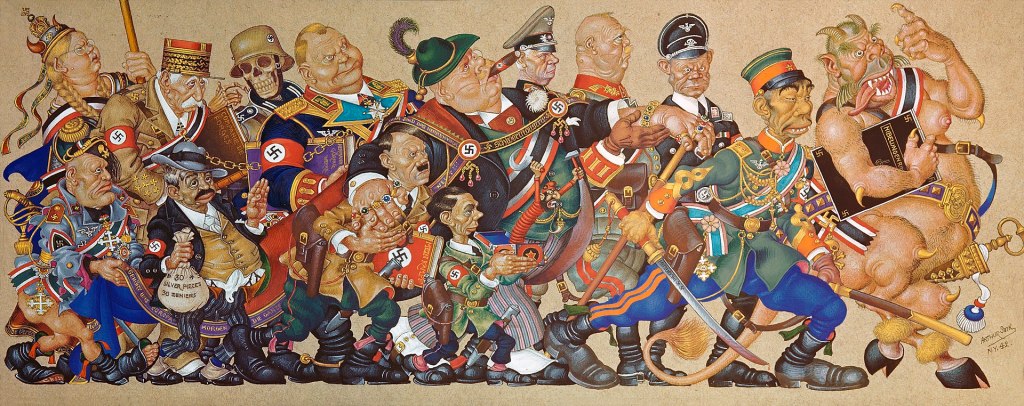

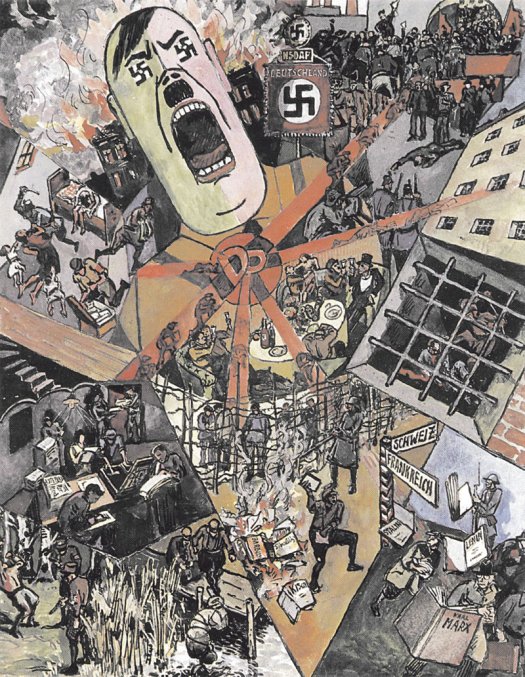

Public Perception and Cultural Representation

- Popular Media and Literature

- Hess’s flight has been dramatised in films, documentaries, and novels, often emphasising its mysterious and dramatic nature.

- These portrayals range from speculative thrillers to more grounded historical narratives, reflecting the enduring fascination with Hess’s actions.

- Memorialisation and Controversy

- Hess’s death in 1987, officially ruled a suicide, sparked renewed interest and conspiracy theories, with some neo-Nazi groups attempting to co-opt his memory as a symbol of resistance.

- Efforts to commemorate Hess have been widely condemned, reflecting his continued association with Nazi ideology.

Conclusion

- Summary of findings:

- Evidence leans toward Hess acting independently of Hitler’s direct orders.

- The Holocaust’s trajectory was unlikely to be influenced by British engagement with Hess.

- Reflections on the historiographical challenges of analysing Hess’s flight.

- Final thoughts on the implications of Hess’s mission for our understanding of Nazi Germany and World War II diplomacy.

Bibliography

- Primary Sources:

- Hess’s prison memoirs and interrogations.

- British intelligence and diplomatic records.

- Secondary Sources:

- Scholarly works on Nazi diplomacy and the Holocaust.

- Biographies of Rudolf Hess and Adolf Hitler.

Conclusion of Historiography and Legacy

Rudolf Hess’s flight to Britain remains a paradoxical event in the history of World War II—both strategically inconsequential and symbolically significant. It highlights the ideological and strategic contradictions within the Nazi regime and serves as a reminder of the complexities of wartime diplomacy. While the mission’s immediate impact was minimal, its legacy endures as a subject of historical curiosity and debate.

Final Reflections: The Mission of Rudolf Hess and Its Implications

Rudolf Hess’s flight to Britain in May 1941 remains a subject of enduring intrigue, encompassing themes of diplomacy, ideology, and the broader trajectory of World War II. This dissertation has explored the historical context, motivations, and consequences of Hess’s mission, engaging with historiographical debates and counterfactual scenarios to assess its potential impact on the war and the Holocaust.

Summary of Key Findings

- Hess’s Mission and Hitler’s Involvement:

- Hess’s flight was a bold yet idealistic endeavor, driven by his unwavering belief in the possibility of Anglo-German cooperation.

- The evidence suggests that while Hess acted in alignment with broader Nazi aims, his mission was not explicitly sanctioned by Hitler. His actions reflected both the ideological cohesion and personal rivalries within the Nazi leadership.

- British Reception and Strategic Implications:

- Churchill’s refusal to engage with Hess underscored the British government’s commitment to total victory and the unlikelihood of a negotiated settlement.

- While Hess’s proposals might have offered short-term strategic benefits to both sides, they were fundamentally incompatible with the ideological and geopolitical goals of the Allies and the Axis powers.

- Impact on the Holocaust:

- The Holocaust was a core element of Nazi ideology, shaped by long-term planning and bureaucratic execution. Diplomatic engagement with Hess was unlikely to alter its trajectory, as it was driven by ideological imperatives rather than pragmatic considerations.

- Historiographical and Ethical Dimensions:

- Hess’s flight illustrates the complexities of historical interpretation, where individual actions intersect with structural forces.

- The ethical dilemmas of engaging with authoritarian regimes remain relevant, highlighting the tension between pursuing peace and avoiding the legitimisation of oppressive ideologies.

Broader Implications for Historical Understanding

- The Limits of Diplomacy:

Hess’s mission underscores the limitations of diplomacy in addressing ideologically driven conflicts. While peace overtures might alter the dynamics of military engagements, they are unlikely to dismantle deeply entrenched ideological systems. - The Role of Individual Agency:

- Hess’s flight exemplifies the interplay between individual agency and structural forces in history. While his actions were dramatic and unprecedented, their impact was constrained by the broader context of Nazi strategy and Allied resolve.

- Historical Memory and Contemporary Relevance:

- The enduring fascination with Hess reflects broader societal interest in the “what-ifs” of history. His mission serves as a reminder of the unpredictability of historical events and the need for careful analysis of their causes and consequences.

Conclusion

Rudolf Hess’s flight to Britain represents a unique moment in World War II history, characterised by ambition, desperation, and futility. It highlights the ideological rigidity of the Nazi regime, the strategic priorities of the Allies, and the human tendency to seek dramatic solutions in times of crisis.

While the mission ultimately failed to achieve its objectives, its legacy endures as a case study in the complexities of diplomacy, ideology, and historical interpretation. By examining Hess’s flight, historians can better understand the intricate dynamics of war and peace, as well as the ethical challenges of engaging with oppressive regimes.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Hess’s Interrogation Reports and Memoirs

- MI5, Interrogation Reports of Rudolf Hess, 1941. National Archives, Kew.

- Hess, Rudolf. Mein Leben für Deutschland (My Life for Germany). Self-published manuscripts.

- Nazi Leadership Documents

- The Wannsee Protocol (1942).

- Goebbels, Joseph. Diaries, 1923–1945. Edited by Elke Fröhlich, German Federal Archives.

- British Government Communications

- Churchill, Winston. The Second World War, Volume III: The Grand Alliance. London: Cassell, 1950.

- Foreign Office Records on Rudolf Hess, National Archives, Kew.

Secondary Sources

- Biographies and General Histories

- Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: A Biography. New York: Norton, 2008.

- Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich at War: 1939–1945. New York: Penguin, 2009.

- Specialized Studies on Hess and the Mission

- Padfield, Peter. Hess: The Führer’s Disciple. London: Cassell, 1991.

- Allen, Martin. The Hitler-Hess Deception. London: HarperCollins, 2003.

- Histories of the Holocaust

- Browning, Christopher R. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

- Friedländer, Saul. Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1933–1945. New York: HarperCollins, 2007.

- Conspiracy Theories and Controversial Interpretations

- Irving, David. The War Path: Hitler’s Germany 1933–1939. London: Papermac, 1978. (Cited critically for historiographical context.)

- McDonough, Frank. The Gestapo: The Myth and Reality of Hitler’s Secret Police. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2015.

Scholarly Articles and Journals

- Barnett, Correlli. “Rudolf Hess: The Enigma of His Flight.” The Journal of Military History, Vol. 34, No. 3, 1970, pp. 289–310.

- Brower, Daniel R. “The Nazi-Soviet Pact and Hitler’s Strategy.” European Studies Journal, Vol. 22, 1999, pp. 14–34.

- Thorpe, D. R. “Churchill’s Response to Hess’s Mission: Pragmatism Over Peace.” Twentieth Century British History, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2016, pp. 561–584.

Documentaries and Media

- Nuremberg: Nazis on Trial. BBC Documentary Series, Episode on Rudolf Hess, 2006.

- The Mystery of Rudolf Hess. Directed by David Irving. Channel 4, 1994.

Online Archives and Digital Resources

- The National Archives, UK: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk (Accessed for declassified MI5 files on Hess).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM): www.ushmm.org (Primary source material on Holocaust policy).

- German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv): www.bundesarchiv.de (Accessed for Goebbels diaries and Nazi-era communications).

An exceptional article, well researched and I am convinced that Rudolf Hess was originally part of the General Stauffenburg Plot which took a number of years in the planning before the German High Command had the courage to follow through!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claus_von_Stauffenberg

Great Photo of Herr Hitler at ze fancy Dress Ball!

DJ Pukeko!

Thank you for your kind words DJ Pukeko…Stauffenberg was a brave man, but rather unlucky….Hitler, however, a very lucky coward.

Jawol!